“A billion here and a billion there, and by and by it begins to mount up into money.”

The origins of this quote are in dispute. Some historians ascribe a version of it to Senator Everett Dirksen (1896-1969), who supposedly said it to Johnny Carson in a taping of The Tonight Show. Others point out that the New York Times printed those words in 1938 in a commentary about the federal budget at the time.

No matter. Substitute “trillion” for “billion” and you’ve got a reasonable preview of today’s article. Do budget deficits even matter for investors any longer? Contributor David Sterman takes a look.

— Bob Bogda, Editor

P.S. Like what you see? Don’t like what you see? Let me know.

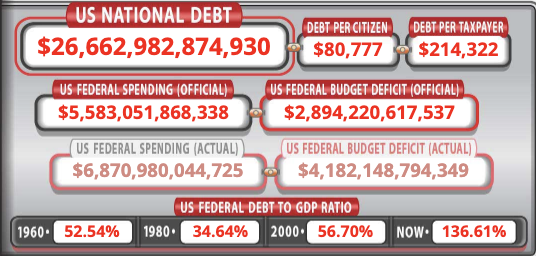

(Source: usdebtclock.org 8/20/2020 at 5:00 pm ET)

In late 2002, Vice-President Dick Cheney allegedly told U.S. Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill that budget “deficits don’t matter.” At the time, Uncle Sam was on the hook for roughly $6.2 trillion, according to Statista.com.

Soon enough, war-time spending would drive the government’s debt tab well higher, as would the vigorous fiscal responses to the Great Recession of 2008/2009. By the time President Barack Obama left office in January 2017, the tide of red ink had surpassed $20 trillion. A staggering sum, by any measure.

Fast forward to 2020, and the spending spigot has turned into a firehose. Through the first 10 months of fiscal 2020 (ended September 30), another $2.81 trillion is being piled on to our nation’s debt, and the total tally stands at $26.6 trillion.

If you want to obsess over this enormous sum, you can watch our nation’s debt levels rising in real-time on this website. As that site notes, the average taxpayer is on the hook for $214,000 in future government debt obligations.

For investors and consumers alike, some key questions need to be asked: Will we ever possibly be able to repay that debt? And does it even matter?

Traditional economic theory suggests that when a borrower takes on more debt than it can pay back, any new borrowings will be made at punishingly high interest rates. That’s the conundrum that “junk bond” issuers often find themselves in.

Curiously, Uncle Sam does not yet appear to be subject to that standard. The yield on 10-Year government Treasuries stands below 0.70%.

Perhaps Dick Cheney was right after all. Two decades on from his nonplussed take on deficit spending, a growing chorus of economists have begun to agree with him, coining a fairly new phrase called Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

This theory states that as long as the U.S. dollar remains as a globally coveted currency, policymakers can write ever larger checks.

Well, not to spoil the party, but MMT has some major holes in it.

First, take note of the caveat that the dollar must remain almighty. Foreign governments both friendly and hostile hold more than $8 trillion of our debt. Should they conclude that the United States is living beyond its means, they may move to pare their government bond exposure and refrain from re-buying fresh bonds once existing bonds mature. The reduction in buyers would, by definition, mean that the U.S. government would have to offer ever-sweeter bond yields to entice other buyers.

This summer’s sharp drop in the dollar (it’s currently trading at the lowest level in more than two years) is a reminder that the currency’s “safe haven” status should never be taken for granted. On July 31, credit rating firm Fitch revised its view of the U.S. economy to “Negative to reflect the ongoing deterioration in the U.S. public finances and the absence of a credible fiscal consolidation plan.”

The second reason why MMT may prove to be mistaken: It depends on the notion that inflation will remain perpetually dormant. Here again, the impact of the dollar plays a role. A falling dollar leads to a direct boost in commodity prices, and rising commodity prices have been a key source of inflation in the past. The surge in gold to all-time highs this summer reflects yet more concern about the future role of the dollar.

SPONSORSHIP

Access granted: See this new market intel in action

By “working” just 30 minutes a day, 3 days a week, people are retiring from their jobs. They’re buying their dream homes, putting their kids through college, and giving back to their communities.

All the details are right here

The third, and perhaps more prosaic reason to be concerned about future deficits involves demographics. The rapid aging of the U.S. population means that the ratio of retirees to working-age citizens will continue to expand. Back in 1945, there were 45 working age Americans for every retiree. That number has been falling ever since and is projected by the Social Security Administration to be just 2.2 by mid-century.

That means that government revenues (through income taxes) will be hard-pressed to keep up with government expenditures. This will make it ever harder to close the budget gap and meaningfully shrink our debt load.

Regardless of your political affiliation, any meaningful moves to stop mortgaging our children’s future will require a cut in government spending and an increase in taxes. The spending part of the equation has truly become the third rail of politics. Fully 28% of national government spending goes to healthcare, another 21% to defense, 24% to pension payments, while the remaining 27% accounts for all of the rest of the government spending. Serious proposals to pare spending have been dead on arrival.

Meanwhile, our annual interest to service the debt stands at $338 billion per year. And that’s in an era of ultra-low interest rates paid by Uncle Sam.

What about taxes? Well, a wide swath of voters would reject any notion of raising taxes on the middle class, which leaves corporations and high-income Americans as candidates to pay a greater share of our nation’s tax bill. In 1945, corporations, for example, paid nearly 40% of all taxes. That figure is below 10% nowadays.

Sadly, this growing problem isn’t raising enough concern among the electorate. Roughly 47% of voters consider the budget deficit to be a very big problem, according to Pew Research. That’s down from 55% just two years ago.

Back in 2018, Barron’s wrote that “deficits don’t matter—until they do.” This is precisely how you should be thinking about this problem. Another way of saying that: The new magical thinking around Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is a wonderful source of debt denial—until it isn’t.

What does this mean to you, the investor? Take note of the fact that a key driver of stock market gains in recent years has been the ongoing drop in interest rates. Yet, when bond markets wake up to the fact our nation’s creditworthiness is becoming questionable, the response will be to push up interest rates.

And you can ask your grandparents what happened to stocks in the 1970s in a backdrop of rising rates. In that decade, the Dow Jones Industrial Average rose less than 5%. That’s a decade-long return, not an annual return.

To be sure, there will continue to be opportunities, almost regardless of the circumstances. As CNBC’s Jim Cramer says, “There is always a bull market somewhere.” And we will continue to help you find one in these pages.

But if you’re “all in” on this remarkable stock market rally, the unfolding economic backdrop and rapidly weakening government finances should encourage you to accept the risk of a much more challenging investment in the years ahead.

SPONSORSHIP

Billionaire Fears America Will End As We Know It

An official government document outlines a coming event that is so shocking a famous billionaire believes this could be the end of America. The good news is this event will also bring with it ample opportunities to build wealth swiftly for those who know how.